South Asian Women’s Creative Collective, A Bomb, With Ribbon Around It. Queens Museum, Queens, New York, 14 December 2013 – 18 January 2014.

A Bomb, With a Ribbon Around It, at the Queens Museum through 18 January 2014, is an eclectic collection of contemporary works from the South Asian Women’s Creative Collective, more commonly known as SAWCC. The show is part of SAWCC’s ongoing work—since its inception sixteen years ago as a grassroots, feminist arts collective in New York—to magnify the voices of emerging and established women artists in the South Asian community. To this end SAWCC, tirelessly produces public readings, film shows, art happenings, and a monthly studio circle throughout the city. SAWCC also works with independent curators to organize an annual exhibition, in step with its mission to bring cutting-edge work that tackles issues of gender and cultural representation to the fore.

This year’s guest curator, Raul Zamudio, opens A Bomb, With Ribbon Around It with a statement that describes the show as including:

works by South Asian women that metaphorically depict the self in personal, social, or cultural guises that will be as attractive, unassuming, and pristine as a beautiful ribbon; yet untying that ribbon triggers an explosion of subject matter that addresses contemporary conditions of globalization manifesting in politics, immigration, gender equality, sexuality, and religion.

In Zamudio’s selection, some works “explode” immediately upon viewing, while others reverberate more slowly and steadily.

Walking into the gleaming gallery space of the recently renovated museum, one is struck by the careful editing of the show, which offers a small but varied sample of artworks. Video, photography, small and large sculpture, painting, and mixed media works are on view, giving the exhibition multiple textures and meanings rather than adhering to a dominant aesthetic or message. A Bomb, With Ribbon Around It challenges viewers to go beyond essentializing and simplifying the creative voices of a particular cultural group, a common trap for curators, practitioners, and viewers of identity-informed art. In the spirit of SAWCC itself, individual voices stand strong to form a picture with many complex parts.

The only video presented, Freedom, Safety, NOW! (2013), is a collaboration of SAWCC artists, filmed and edited by Shruti Parekh. The video is a documentation of the collective’s creative intervention at the Indian Consulate in New York in January 2013, to bring attention to the horrific gang rape and subsequent death of Jyoti Singh Pandey and the assault on women’s bodies everywhere. The video is shown as an installation, its monitor hung against a floor-to-ceiling wallpaper of bold letterpress posters. Because no text is offered explaining who or what SAWCC is, this video serves to ground the exhibition by showing, rather than telling, a key component of their work. The video activates the space, and the urgency and directness of its message provides a counterpoint to the stillness of the other pieces in the exhibition.

[Installation view of "Freedom, Safety, Now!" (2013) by Shruti Parekh. Photograph by the author.]

[Installation view of "Freedom, Safety, Now!" (2013) by Shruti Parekh. Photograph by the author.]

Across from the installation, Jaishri Abichandani’s set of miniature sculptures, Before Kali (2013), scream out at the viewer. A series of small, ceramic hybrid goddesses—part animal and plant form, part archetype—each miniature sculpture can stand in the palm of one’s hand, yet their energy is that of forces much bigger. They are individually poised on handmade stands, jutting out of the white wall in a slight pyramid shape, hung just below eye level. This arrangement gives the viewer an intimate experience of these small yet fierce figurines.

Mona Kamal’s Alluring Friction (2013) presents the viewer with a life-size rustic wooden bed frame. The frame is a rugged design, not common to contemporary middle-class life, and the mattress is replaced by a tangle of golden barbed wire. The piece evokes a visceral response and conjures feelings of both desire and alienation. The form of a bed creates associations of warmth, comfort, and rest, which are immediately thwarted by the threat of the barbed wire. Information available on the artist’s website, but not presented in the exhibition, reveals that this is a Charopy, a traditional Indian bed typically woven with rope, commonly found in both India and Pakistan. This information, which the curator unfortunately excluded, gives the object another dimension of meaning, alluding to the charged relationship between India and Pakistan.

Without a bio or artist statement for a piece like Mona Kamal’s, multiple layers of meaning and important content can be missed. Pieces take on an entirely new set of meanings when culturally specific information is offered, either in the artist’s own words, or in the curator’s presentation. For the works to have their full impact, and in order to create the “explosion of subject matter that addresses contemporary conditions of globalization,” having access to contextual information is key, particularly for a non-South Asian audience. It is not always easy to strike the right balance between showing and telling, but including such cultural nuances in the form of wall texts would only enrich viewers’ understandings of the exhibition as a whole.

References to the body and gender are reflected in several featured works. Nazneen Ayyub-Wood’s Uninvited Pest (2013) spooks viewers from afar, appearing as a life-size enshrouded black figure oddly protruding out of one of the gallery’s white walls. Upon closer inspection, we see child-like fairy wings attached to this black costume, and a pair of silver Cinderella slippers, placed on the floor beneath the figure—as if they have just slipped off. The costume hangs from two large Velcro strips, loosely mimicking a flytrap. The uninvited pest seems to be a make-believe kind of superheroine who has just escaped her make-believe trap, leaving her costume behind. During the opening of the exhibition, the artist slipped into the attached costume and adopted the role of the clinging figure, punctuating the room as viewers encountered her contorted body. The performative part of this piece was only evident to viewers who attended the opening, since there is no documentation of the performance installed alongside the work.

[Nazneen Ayyub-Wood performing at the exhibition opening. Image courtesy of SAWCC.]

[Nazneen Ayyub-Wood performing at the exhibition opening. Image courtesy of SAWCC.]

In Beena Azeem’s large-scale canvas Chaos Theory (2012), mirrors collapse the picture plane of a large canvas filled with male and female bodies. The space of the painting becomes a stage for these performers, who somehow act out various roles. There is a voyeuristic aspect to viewing these nearly nude figures, and suddenly their inner lives become more accessible than that of the classic nude, an overplayed subject in painting. By presenting these characters partially undressed as if in prayer or mid-ritual, Azem disarms them and makes them more familiar to the viewer, whereas “the nude,” an artistic invention, creates a distance between art and life.

[Installation view of Beena Azeem`s Chaos Theory (2012). Image courtesy of SAWCC.]

[Installation view of Beena Azeem`s Chaos Theory (2012). Image courtesy of SAWCC.]

More conceptual works, like those of Shelly Bahl and Swati Khurana, provide spaces to reflect on the nature of representation and communication. Bahl’s International Woman of Mystery (2012), small hand-drawn pictures of movie stars on a scroll of patterned paper, leaves the viewer wondering who these women really were, raising questions about representations of “exotic” women on screen and in real life. Khurana’s ongoing series of transcribed text messages is presented as a magnified typed text, snaking across the top corner of two walls. It is a fragmented message, which conjures up ideas about the changing nature of intimacy in the digital age.

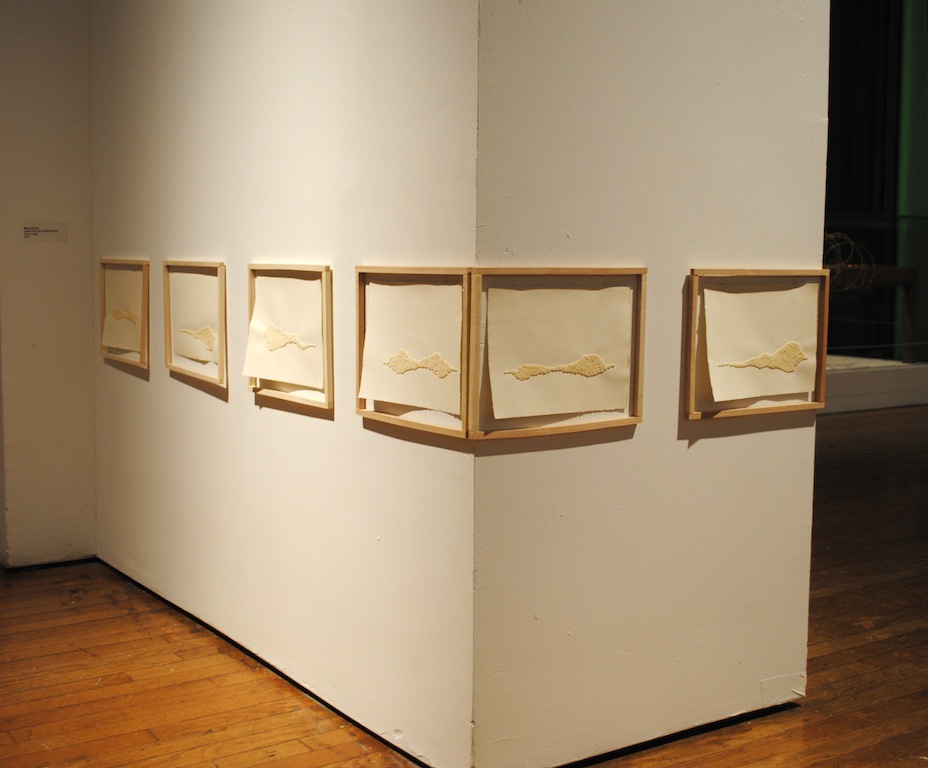

Marcy Chevali’s Swallowed series (2012), a set of drawings created with grains of dry rice formed into tightly knit, amorphous organic shapes on paper, whisper across a wall and hang close to the floor. In their intimate scale and use of simple organic materials, they evoke the movement of breathing or swallowing, or other internal bodily rhythms, or perhaps the tedious meditative work of sorting grains.

[Installation view of Marcy Chevali`s Swallowed series (2012). Image courtesy of SAWCC.]

[Installation view of Marcy Chevali`s Swallowed series (2012). Image courtesy of SAWCC.]

Overall, A Bomb, With Ribbon Around It offers audiences a small but loaded selection of art. Issues of gender, cultural exotification, immigration, religion, and politics are addressed, more directly in some works than others. From the sobering reminder and call to action of Freedom Safety NOW! to the humorous bronze of a blinged-out semi-Hindu-goddess Diva (2013) by Siri Devi Khandavilli, the realities of our globalized world are not contained in what is local and cannot be captured with one type of mood or aesthetic response. As artists in diaspora, these women are grounded in more than one place, and in multiple histories, herstories, languages, and continents. They have personal access to an incredible array of visual languages and personal and political content to fuel their work. From the diversity of strategies present in this exhibition, it is clear that this art is not here to serve a monolithic view of culture, but to lead us into a world of questioning more deeply how culture affects us, and how we continually reinterpret culture.